What's The Most Valuable Company In History? Apple? Google? Maybe Exxon? These would all be very good guesses. As of this writing, Apple is the most valuable company in the world today, with a market cap of $1.8 trillion. Apple topped that $1 trillion market cap milestone for the first time in 2017. Pretty impressive, right? Well, can you imagine a company that was worth $7.4 trillion?

No matter how successful a company like Apple or Exxon is today, they are still a far cry from being the most valuable company in history. That title belongs to a little operation called The Dutch East India Company. It seems like a ridiculous number, but at one point, The Dutch East India Company was worth a mind-boggling $7.4 trillion. Widely recognized as the first multinational corporation, the Dutch East India Company's reach and power make today's major corporations look like small potatoes. The first corporation of its kind, the Dutch East India Company provided the framework on which all other conglomerates have been built ever since. The company's rise, and eventual fall, is both a lesson in business management and a major cautionary tale.

MAURICE AMOUREUS/AFP/Getty Images

The necessity for a Dutch trading company came about after Portugal cut Dutch merchants out of their Asia to Europe trade agreements. The Dutch Revolt in the late 1500s had severed Spain's control of the northern portion of the Netherlands. Since Portugal was an ally of Spain, this put a definite damper on trade between the two countries. The ugly politics, combined with the fact that it was cheaper for Portugal to deliver spices to Europe via Hamburg, resulted in the Dutch being cut out of the major trade routes. However, it quickly became clear that Portugal was not able to meet the demand for spices, so Dutch merchants began sending their own ships out.

The new Dutch traders began with some major advantages. Many of the Portuguese trade routes had been sailed by Dutch captains, so they had the knowledge and the contacts in place already. Over the course of the next five years, larger and larger expeditions were sent out by various merchants. While some crews perished due to pirate attacks, attacks from the Portuguese, and storms, many were able to make the trip successfully. The merchants began forming alliances with various small islands along the route, securing monopolies on the spices grown on the islands. More importantly, they secured the support of the indigenous peoples, essentially hiring them to harass/attack merchants from other countries who were sailing the same routes.

The British increased pressure on all merchants, when they formed the first monopoly enterprise in the 1600s. Instead of investing in each expedition individually, English merchants, backed by the crown, were now sending out massive expeditions with combined resources. In order to stay competitive, the Dutch formed the Dutch East India Trading Company in 1602. Backed by the Dutch government, the Dutch East India Trading Company came to monopolize trade with Asia. The heads of the company were also allowed to create treaties with Asian countries and islands along the trade routes. More importantly, they were allowed to form armies and build fortifications in order to defend those trade routes from other countries. The Dutch East India Company, was, for all intents and purposes, its own country – a country whose sole purpose was to make the Dutch government, and private investors, richer. The Dutch East India Company and the British trading companies eventually banded together in 1620, but by 1623, everything had fallen apart. The whole mess came to a head when twenty tradesman, ten of whom were British, were arrested, tortured, convicted, and beheaded on charges that they were conspiring against the Dutch government. The British withdrew from the trade routes they shared with the Dutch, and the Dutch East India Company continued its rapid expansion with very little resistance.

The head of the Dutch East India Company during this time was a man named Jan Pierterszoon Coen. Mr. Coen had major ideas about how the company should expand and he refused to let anything stand in his way. The Dutch became ruthless about establishing control of their trade routes, and each successive head of the company followed the example set by Mr. Coen. By 1669, the Dutch East India Company had 150 ships for trade, 40 warships, a private army of 10,000, and 50,000 employees. The company's success had made the original investors unimaginably rich, as the company now boasted a dividend payment of 40%. At the peak of their power in the mid 1600s, accounting records showed that the company valued itself at 78 million Dutch Guilders. When adjusted to modern dollars after inflation, that's equal to $7.4 trillion.

However, all good things must come to an end, and such is the case with the Dutch East India Company. The problems began in the early 1700s, when multiple small wars interrupted trade routes. Then the spice trade began to dry up. The Dutch had always very carefully controlled the spice market, especially the pepper market, by always having just a little too much pepper available. This made it difficult for other countries to make a profit selling pepper because the oversupply depressed the market slightly. If anyone else tried to get a spice trade going, believing that the market would eventually shift, they found themselves disappointed and poor. The Dutch East India Company, which was very wealthy at this point, would simply wait them out. This plan worked quite well until the demand for spices from Asia began to disappear. Suddenly, they had to diversify, and the economics of their new products – cotton, sugar, tea, and coffee, could not match the money they'd made via the spice trade. They'd also spent a great deal of money setting up armies and securing treaties. However, multiple smaller companies began forming more lucrative treaties with islands and market hubs that had originally been loyal to the Dutch.

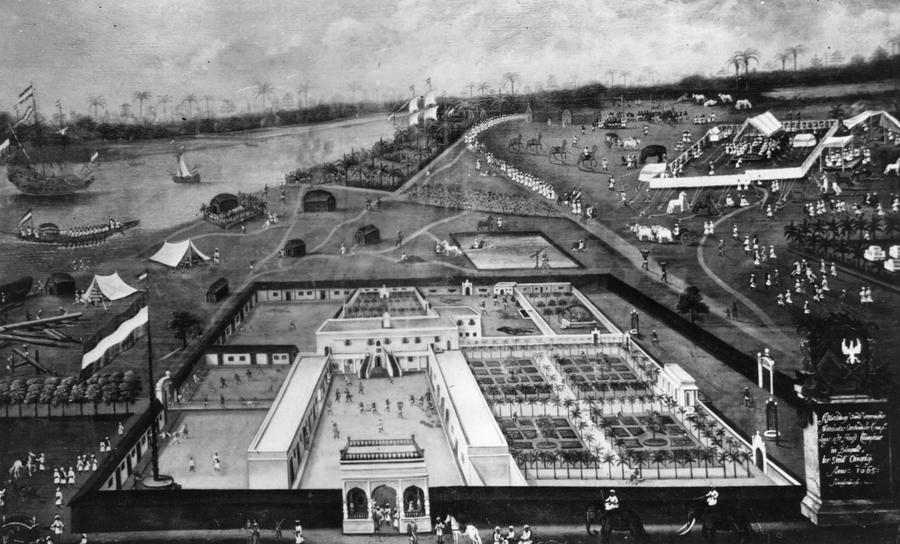

The central offices of the Dutch East India Company at Hugli, in Bengal, India. Circa 1665:

Getty Images

By the 1780s, the Dutch East India Company had become a house of cards. Trade and trade routes were diminishing. Though the Dutch East India Company was massively successful, its employees were paid very little. (Sounds like every major company today, doesn't it?) Consequently, smaller factions within the company were stealing profits, whenever, and wherever they could. Combine all that with the fact that employees died – all the time – due to shipwreck and attacks, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to hire anyone to work for them. Additionally, the company was slow to change with the times. They'd always brought all of their products to one central location in Batavia, and then distributed everything from there. Other companies began going straight from Asia to the port with the most demand for the particular products they were trading. The Dutch East India Company simply couldn't keep up, because they had an intermediary stop. Finally, their high dividend payments eventually exceeded their profits. In fact, the company was soon in debt, because its high dividend payments had exceeded their profits for all but 10 years of the company's existence. The company was surviving on anticipatory loans, but with all of the problems, they started to buckle. By 1799, the Dutch East India Company was no more. All of the islands and small nations that it had controlled were divided between the Dutch and the British after the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s, and that was that.

Over the course of two hundred years, the Dutch East India company went from four ships on an exploratory expedition, to the most successful business ever, to bankruptcy. Looking at its history, it's easy to see that the company simply grew too big, too fast. It is proof that it is possible to be too successful, too multinational, and dare we say, too greedy. Will the big oil companies, big media conglomerates, and big technology firms of today find themselves crumbling under the weight of their own expansion someday? Will any company ever grow to be worth $7.4 trillion again? The answer is probably no. Yes, the Dutch East India Company provides a great example of how to grow a business. However, it also provides an excellent example of how to run it into the ground. The latter seems to be the lesson to which most business people have paid attention.

/2015/02/cook.jpg)

/2017/11/cook.jpg)

/2014/11/GettyImages-106544513.jpg)

/2021/11/elon2.jpg)

/2014/09/Waddesdon-Manor.jpg)

/2014/09/John-D.-Rockefeller.jpg)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/P-Diddy.jpg)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)