Michael Milken is one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in finance history. Never heard of him? Consider this: How many people can say they a) spearheaded a financial revolution, b) earned more money than anyone else in America several years in a row, c) eventually became a multi-billionaire, d) got arrested and sent to jail… AND e) got a Presidential pardon???

From his X-shaped trading desk in the heart of Beverly Hills, Michael Milken engineered a revolution in corporate finance by popularizing high-yield "junk" bonds. His innovations fueled a generation of risk-taking, turbocharged the merger and acquisition boom, and helped transform obscure upstarts into corporate titans. And then he went to jail.

But he did have a second act…

The Rise of a Future Junk Bond King

Michael Milken was born in Encino, California, in 1946. He showed early promise as a student, attending Birmingham High School, where actress Sally Field was one of his classmates, and was elected prom king. He went on to earn a business degree from the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with high honors in 1968. He then pursued an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, where he developed a fascination with low-grade corporate bonds.

In 1969, after completing his MBA, Milken joined Drexel Harriman Ripley (soon renamed Drexel Burnham Lambert). He was tasked with overseeing low-grade bond research, a relatively obscure niche. Milken believed that so-called "junk bonds" were undervalued and underutilized, and he set out to prove it. He quickly generated astronomical returns, often exceeding 100 percent annually.

By 1976, Milken was earning $5 million a year as a salary. That's the same as $30 million in today's dollars. And as if that salary wasn't amazing enough, in 1976, he also got a $5 million bonus. So in modern dollars, the 30-year-old made around $60 million that year.

He relocated his operations to Beverly Hills and created an X-shaped trading desk that became the nerve center of the junk bond world.

"Highly Confident" Letters

Milken's influence was so great that Drexel could issue so-called "highly confident letters," essentially informal promises that financing would be available.

Imagine you want to buy a $20 million house but don't actually have $20 million in your bank account. So you walk into your local Bank of America. The bank likes you, so they write a letter to the seller that says, "We are highly confident we can find $20 million for this buyer." The seller agrees to the deal, trusting the bank's word. After the deal is accepted, the bank raises the funds by selling debt to investors. You, the home buyer, now owe interest on that $20 million loan, but that's fine—because you immediately convert the mansion into four luxury apartments and sell each one for $6 million. You walk away with $24 million, pay back the loan, and pocket a couple million in profit.

That's essentially what Milken and his team did over and over, only instead of houses, they were financing billion-dollar corporate takeovers.

One of the most famous examples was the 1988 takeover of RJR Nabisco, a $25 billion deal that, at the time, was the largest leveraged buyout in history. When private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR) needed a massive infusion of capital to outbid rival suitors, Drexel issued a highly confident letter promising the funds, even though the capital hadn't yet been raised. That single letter helped swing the deal in KKR's favor and solidified Drexel's reputation as the undisputed king of junk bond financing.

The Highest Paid Person in America

Thanks to Milken's high-yield bond machine, Drexel became one of the most profitable investment banks in the country, despite being a relatively small player compared to traditional powerhouses like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley. The firm's junk bond department, headquartered not in New York but in Beverly Hills, was generating hundreds of millions in profits. And Milken, its architect, was the highest-paid person in American business.

His earnings were almost mythological.

- In 1984, he reportedly made $122 million, the equivalent of roughly $370 million today.

- In 1986, he pulled in $296 million, or about $790 million adjusted for inflation.

- And in 1987, he hit his peak: $550 million in a single year, worth over $1.4 billion in today's dollars.

That success translated into incredible power. Milken had his own orbit of loyal investors, clients, and rising corporate raiders who depended on his capital to fund their deals. Companies that couldn't raise a dime through traditional bank loans turned to Milken's junk bond shop, and he delivered. He financed startups, fueled hostile takeovers, and helped build modern corporate empires. To his admirers, he was unlocking growth and democratizing access to capital. To his critics, he was flooding the market with risky debt, destabilizing companies, and enabling a wave of greed-fueled consolidation.

ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty Images

The Crash

The highly confident letters, the junk bonds, the mountains of leverage… it all worked brilliantly, until it didn't. For much of the 1980s, Milken's model relied on a simple but powerful premise: use high-interest debt to buy a company, then restructure, downsize, or sell off assets to pay down that debt quickly. As long as companies were able to refinance, slash costs, or spin off divisions at a profit, the system kept humming.

But the moment those companies stopped making their payments, the music stopped.

Going back to the home purchase analogy – When the system is humming and a $20 million house easily converts into four $6 million apartments, everything works out. But as those easy deals dry up, more speculative investors try to take a crack at the game. They want to offer $40 million for the same house, hoping it can be quickly converted into four $12 million apartment units. But the apartment market has soured.He defaults on his loan. The banks that lent him the money were counting on that money to cover a different default. Yada yada yada, the system seizes up, then crashes.

By the late 1980s, the market for junk bonds had become dangerously saturated. Milken's deals had grown larger, more aggressive, and more speculative. The interest rates were high. The leverage was extreme. And the margin for error was razor thin. Companies that were once touted as visionary acquisitions began to falter under the weight of their debt. Defaults increased. Investors who had previously lined up to buy Drexel's bonds started to back away.

The broader markets began to feel the strain. On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 22% in a single day. Known as Black Monday, it remains the largest one-day percentage drop in U.S. stock market history. For comparison, the crash of 1929 that triggered the Great Depression saw a 12.8% drop on its worst day, and the 2008 financial crisis caused a 7.9% drop at its steepest.

The crash rattled investor confidence and exposed just how fragile the financial system had become. Companies that had borrowed heavily in the junk bond boom suddenly found themselves unable to refinance. Panic spread, and defaults began cascading through the system. The junk bond market, once Milken's playground, became a battlefield of collapsing deals and disappearing liquidity.

The Fall of Milken

In March 1989, Milken was indicted on 98 counts, including racketeering and securities fraud. The charges alleged a pattern of criminal behavior that had permeated Drexel's junk bond operations. Facing a potential life sentence, Milken struck a plea deal. He pleaded guilty to six felony counts of securities and reporting violations.

In 1990, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison and ordered to pay $600 million in fines and restitution. He served just 22 months before being released for good behavior, but the damage was done. He was permanently banned from the securities industry, his reputation in ruins.

Milken emerged from prison in 1993 to face another battle: a diagnosis of advanced prostate cancer. It was a turning point. Confronted with his mortality, Milken pivoted from finance to philanthropy. He founded the Prostate Cancer Foundation and began pouring his energy and remaining wealth into medical research.

He didn't stop there. He launched FasterCures to improve how medical treatments are developed, co-founded the Melanoma Research Alliance, and began making significant investments in education. In 1996, he helped launch Knowledge Universe, a venture in early childhood education. He also became a major backer of K12 Inc., a pioneer in online learning.

Rebuilding

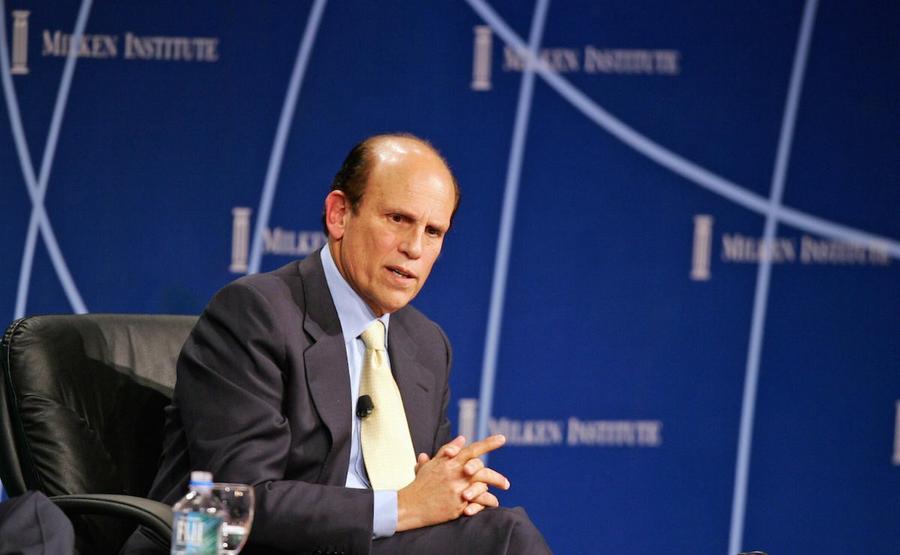

In 1998, Milken founded the Milken Institute, a think tank focused on economic policy, health, and education. The institute's annual Global Conference became a who's who of business, politics, and academia.

His philanthropic footprint expanded rapidly. The Milken Family Foundation gave millions to support innovative teaching. In 2014, George Washington University renamed its public health school the Milken Institute School of Public Health after an $80 million donation.

In 2020, President Donald Trump granted Milken a full pardon, wiping his record clean. Today, Michael Milken's net worth is $6 billion. And that's AFTER he has donated over $1.5 billion to medical research, education, and policy work. His legacy had been largely rehabilitated, but not without controversy.

To some, Milken is a visionary whose innovations in high-yield finance opened doors for companies and investors alike. To others, he is a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked ambition and the ethical cost of financial wizardry. His own reflections are cagey. "I don't believe people really change," he once said. "I was the same guy at Berkeley as I am now."

Whether that's true or not, Michael Milken remains one of the most compelling and controversial figures in modern financial history. His story is equal parts brilliance and excess, innovation and transgression. It is, ultimately, a reminder of what can happen when financial genius collides with moral ambiguity.

/2009/10/Michael-Milken.jpg)

/2022/04/nicola-nelson.png)

/2010/07/np.jpg)

/2013/04/Antony-Ressler.jpg)

/2021/02/gibson.jpg)

/2014/02/Marc-Rowan-1.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/P-Diddy.jpg)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)