When the average person gets fired, they're handed an empty box for their belongings and MAYBE a month of severance. Getting fired in the upper echelons of corporate America is a little different.

Take Bob Chapek, for example. He served as CEO of Disney from February 2020 to November 2022. That's roughly two years and nine months. For his efforts, Chapek was given a $20 million going-away present, also known as a "golden parachute." Can you imagine getting $20 million for doing a bad job? Such a bad job that you get fired after a relatively short period? FYI, Bob worked a little over 1,000 days of work. That breaks down to roughly $38,461 per working day.

Pretty amazing, right? Well… $20 million is a drop in the bucket compared to what a different Disney executive earned 30 years ago for working half as long…

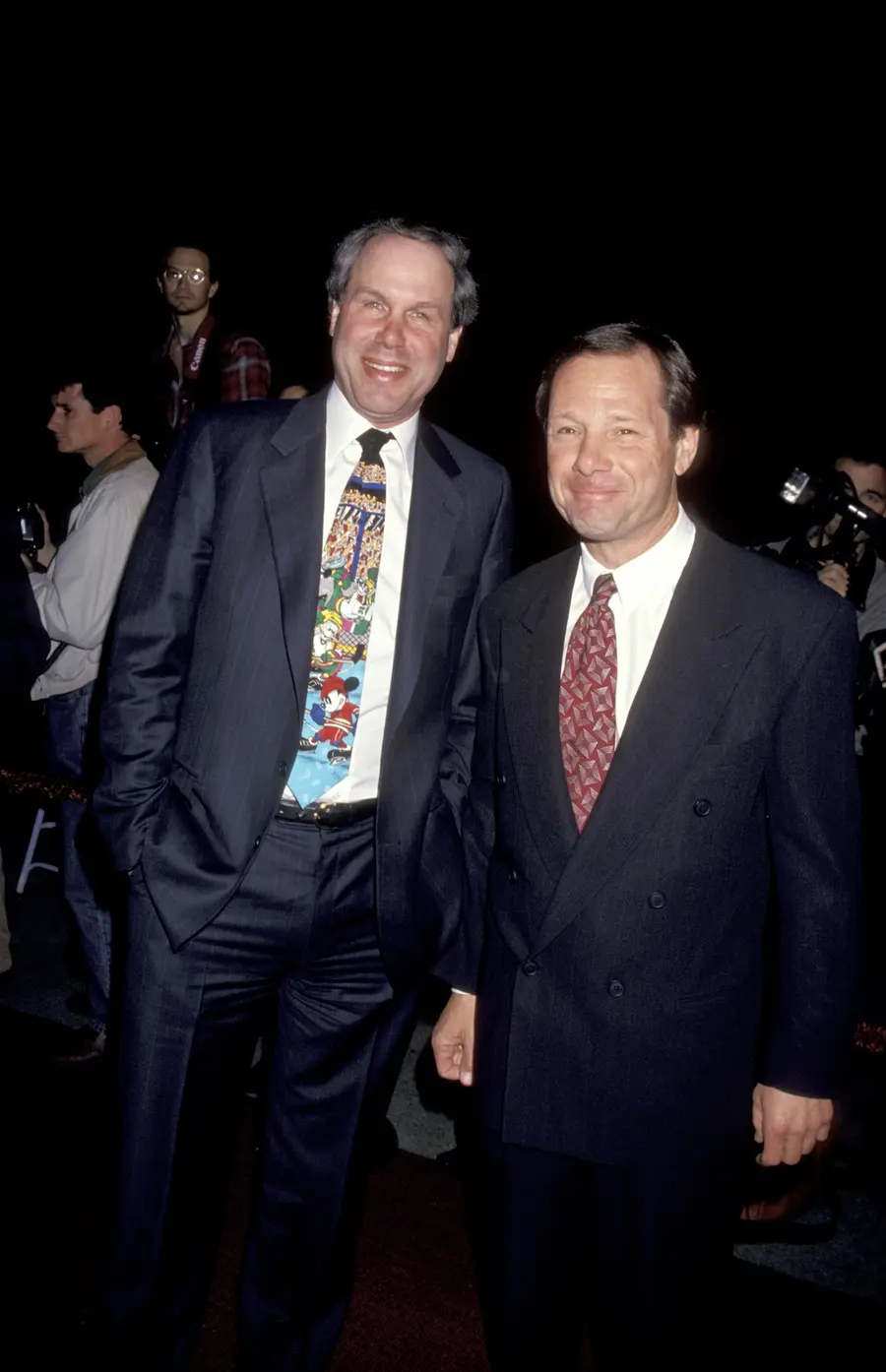

Michael Eisner (left), Michael Ovitz (right) in 1994 (Photo by Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Creative Arts Agency

Michael Ovitz got his start in the entertainment industry as a part-time tour guide at Universal Studios while attending UCLA. After graduating in 1968 with a degree in theater, film, and television, he joined the William Morris Agency, starting in the mailroom and eventually rising to become a successful television agent.

Frustrated by limited pay and stalled promotions, Ovitz and four colleagues began planning their own agency. When William Morris caught wind of the plan in early 1975, the group was fired. Undeterred, they launched Creative Artists Agency (CAA) later that year.

Ovitz hit the ground running—reportedly closing three film packaging deals in CAA's first week. Within four years, CAA had become the third-largest talent agency in Hollywood, generating $90.2 million in annual bookings. Ovitz served as president and later chairman, representing an elite roster of clients including, Tom Cruise, Dustin Hoffman, Kevin Costner, Barbra Streisand, and Steven Spielberg.

Beyond talent deals, Ovitz played a pivotal role in high-stakes corporate negotiations. He helped orchestrate Sony's acquisition of Columbia Pictures, brought Coca-Cola on as a CAA client, and was instrumental in guiding David Letterman's jump from NBC to CBS.

Disney Calls

Bottom line: In the late 1980s and early 1990s, CAA was the most powerful agency in Hollywood, and Mike Ovitz was arguably the most powerful person in the entire entertainment industry. He was equal parts idolized, envied, feared, and respected. He made many enemies both inside and outside his own agency. He also found himself overseeing a machine that required his acute attention all day, every day, 365 days a year. Clients were needy. Studios were greedy and cheap. Young partners at CAA wanted their own shot and saw Ovitz as blocking them.

By 1995, Ovitz was ready to do something else. He wanted to leave the agency world and take a fat corporate job where he would fly around on a corporate jet, earning huge sums of money from stock options. He wanted a position where he controlled the purse strings, instead of trying to convince someone else to open their checkbook for a client.

In what must have seemed like perfect timing, one of Ovitz's longtime friends, Disney chairman Michael Eisner, came calling with an extremely attractive offer. Eisner made it clear that he wanted Ovitz to be his heir apparent at Disney. Eisner intimated that Ovitz would spend a year or two learning the ropes, then take over as CEO when he rode off into the sunset.

Michael Ovitz was announced as Disney's new Executive President in October 1995.

Before agreeing to the job, Disney and Ovitz worked out a compensation package that would later be the subject of a years-long court battle because of what happened next.

No-Fault Golden Parachute

When Ovitz left CAA, he walked away from $200 million worth of guaranteed future commission fees. To make him whole, Disney agreed to a "no-fault" golden parachute: if things didn't work out for any reason, Ovitz would still walk away with a massive payout.

That clause would prove to be very important, very soon. Probably infinitely sooner than anyone could have possibly imagined.

Not What He Signed Up For

Almost immediately, it became clear the job wasn't what Ovitz had expected. As Executive President, he was supposed to be Michael Eisner's right-hand man, but the role lacked clear authority and defined responsibilities. Ovitz found himself floating between departments, wielding far less power than he had at CAA—where every decision had once run through him.

Worse, Ovitz and Eisner clashed constantly. What had been pitched as a seamless partnership quickly turned combative. Ovitz grew frustrated by his limited influence and inability to implement meaningful change.

Worst of all, Ovitz quickly discovered that Eisner had no intention of leaving the CEO post any time soon, and he was certainly not the presumed heir-apparent. As would turn out, Eisner did not step down as CEO until September 2005, a full decade after Ovitz was first convinced to join.

After months of bitter infighting, in January 1997, Michael Eisner fired Michael Ovitz. In total, Ovitz worked at Disney for 1 year and 3 months.

His replacement? A rising Disney executive who had quietly waited in the wings: Bob Iger.

Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images

Massive Exit Package

When Michael Ovitz was fired in January 1997, he certainly didn't leave empty-handed. Thanks to the no-fault clause in his contract, Disney was obligated to pay him $138 million. The payment consisted of $38 million in cash and $100 million in Disney stock.

That works out to roughly $300,000 for every single calendar day he spent employed at the company. And if you narrow it down to just business days—Monday through Friday—Ovitz effectively earned about $445,000 per workday.

And this was back in 1996 dollars.

After adjusting for inflation, his payout today would be worth closer to $280 million. Or to put it another way: in today's money, Ovitz made nearly $900,000 a day for his 14-month Disney stint.

Legal Loophole

When news of the payout became public, Disney shareholders were livid. Many assumed it was a severance package—a lavish reward for someone who had failed at his job. A group of shareholders sued then-CEO Michael Eisner and Disney's Board of Directors, accusing them of gross mismanagement and fiduciary irresponsibility.

But here's the key distinction: it wasn't severance.

Ovitz's payout had been part of the original hiring deal—intended to lure him away from Creative Artists Agency, where he was walking away from an estimated $200 million in future commissions and long-term earnings. This was Disney's way of making him whole if the role didn't work out, regardless of fault.

That detail ended up being crucial in court. In 2005, after a years-long legal battle, a Delaware Chancery Court sided with Disney, clearing Eisner and the board of any wrongdoing. In a pointed but ultimately exonerating 175-page opinion, the judge wrote:

"Despite all the legitimate criticisms that may be leveled at Eisner, especially at having enthroned himself as the omnipotent and infallible monarch of his personal Magic Kingdom, I nonetheless conclude, after carefully considering and weighing all the evidence, that Eisner's actions were taken in good faith."

Did Disney wish it could have used Eisner's services for longer than a year? Obviously. But that didn't matter. The contract was clear, and the check was deposited.

FYI: If Michael had held on to those $100 million shares to mid-2021, when Disney stock hit an all-time high of $190, they would have been worth nearly $1 billion. Imagine making $1 billion from a job you got fired from after a year 🙂

/2011/03/Michael-Ovitz.jpg)

/2009/10/Michael-Eisner.jpg)

/2022/03/ari-emmanuel.jpg)

/2022/12/elon-richest.jpg)

/2014/05/GettyImages-151182287.jpg)

/2022/10/Vijaya-Gadde.jpg)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/P-Diddy.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)