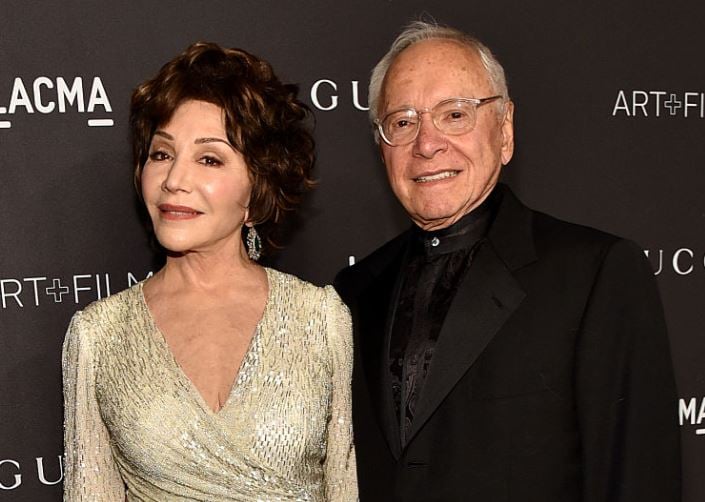

What is Stewart and Lynda Resnick's Net Worth?

Stewart and Lynda Resnick are an entrepreneurial couple who have a net worth of $8 billion. Stewart and Lynda Resnick earned their fortune thanks to their privately held conglomerate, The Wonderful Company, which owns a range of popular consumer brands, including FIJI Water, POM Wonderful, Wonderful Pistachios, Halos Mandarins, JUSTIN Wines, Landmark Vineyards, and Teleflora. Over the past four decades, the Resnicks have quietly built one of the most successful food and beverage empires in the United States, with estimated annual revenues exceeding $6 billion. In addition to their business ventures, the couple has also become known for their large-scale philanthropy, funding major initiatives in education, climate science, and the arts.

While they are largely publicity-shy and rarely give interviews, Stewart and Lynda Resnick rank among the richest self-made couples in the world, with business interests that span agriculture, water infrastructure, floral delivery, and luxury goods. Their rise from modest beginnings to billionaire status is a uniquely American success story.

Early Life and Background

Stewart Allen Resnick was born in 1936 in New Jersey. He earned a bachelor's degree in business administration from UCLA, followed by a J.D. from UCLA Law School in 1962. He briefly practiced law before shifting into entrepreneurship. In the late 1960s, Stewart began acquiring and operating businesses, starting with janitorial services and moving into security systems with a company called American Protection Industries.

Lynda Rae Harris was born in Baltimore and raised in Philadelphia. She studied journalism and marketing and began her career in advertising. In 1969, she founded her own advertising agency, Lynda Resnick Advertising, and built a client roster that included high-profile brands and political campaigns. The couple met in the early 1970s, married in 1973, and soon began collaborating on business ventures. Lynda brought marketing savvy and branding expertise; Stewart focused on operations and acquisitions.

The Creation of The Wonderful Company

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Resnicks quietly began acquiring agricultural and consumer product businesses in California's Central Valley. They purchased Teleflora, a floral delivery service, in 1979, and in the early 1980s acquired Franklin Mint, a producer of collectibles. But their biggest wins came in agriculture.

In 1981, the couple purchased Paramount Citrus, a sprawling citrus business in California. Over time, they expanded their holdings to include pistachios, almonds, and pomegranate orchards, transforming the Central Valley into a vertically integrated agricultural hub.

Their holdings were eventually unified under Roll Global, which they later renamed The Wonderful Company in 2015. Today, the company is one of the largest privately held agricultural conglomerates in the world, managing more than 135,000 acres of farmland in California and Texas.

The Wonderful Company's core brands include:

- FIJI Water – Acquired in 2004, now one of the best-selling imported bottled water brands in the U.S.

- POM Wonderful – Pomegranate juice company launched in 2002 after the Resnicks began planting thousands of acres of pomegranate trees.

- Wonderful Pistachios & Almonds – One of the largest producers and marketers of pistachios and almonds in the world.

- Wonderful Halos – Market-leading brand of California-grown mandarins.

- JUSTIN Vineyards & Winery and Landmark Vineyards – Premium wine labels focused on Paso Robles and Sonoma Valley varietals.

- Teleflora – A floral wire service with a network of 10,000 florists across the country.

The company has also invested heavily in vertical integration. They control their own packaging plants, bottling facilities, marketing, and even trucking. This has enabled them to build efficient supply chains and control branding from farm to shelf.

Getty

Marketing Mastery

Lynda Resnick has played a central role in building The Wonderful Company's brand identity. Her early advertising work helped shape the marketing of POM Wonderful and FIJI Water, both of which relied on sleek packaging, health-focused messaging, and savvy partnerships.

POM Wonderful, in particular, became a cultural phenomenon in the early 2000s. The juice's distinctive bottle design and bold health claims—later challenged by the FTC—helped catapult pomegranate juice into a $100 million business. Lynda also helped launch quirky, high-visibility campaigns for Wonderful Pistachios, including celebrity-endorsed ads and Super Bowl commercials.

Lynda published a book in 2009 titled "Rubies in the Orchard", which detailed her branding philosophy and the Resnicks' path to building iconic consumer brands.

Real Estate Holdings

The Resnicks have assembled a vast real estate portfolio, with properties in Beverly Hills, Aspen, and Hawaii. Their most high-profile asset is a 74-acre estate in Aspen called Little Lake Lodge. In September 2025, the property was listed for sale for $300 million, making it the most expensive home on the U.S. market at the time. The 27,000-square-foot compound includes 18 bedrooms, 20 bathrooms, a six-acre private lake, and direct access to hiking and ski trails.

They also own a historic estate in Beverly Hills, and in 2019, it was reported that they had purchased additional land in Kauai, Hawaii.

Philanthropy

The Resnicks have donated more than $2.5 billion to various causes, with a focus on education, climate research, health, and community revitalization.

Their largest gift came in 2019, when they pledged $750 million to Caltech to support environmental sustainability and climate research. It remains one of the largest donations ever made to a U.S. academic institution.

They have also contributed:

- $100 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

- $50 million to UC Merced

- $30 million to the Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA

- Tens of millions to community projects in California's Central Valley, including schools, parks, and wellness centers

They established the Wonderful Education initiative, which offers scholarships, mentoring, and job placement to students in farming communities served by their company.

California Water Controversy

Stewart and Lynda Resnick's control of water rights in California has long been one of the most controversial aspects of their business empire. While they have helped turn the Central Valley into one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world, critics argue they've done so in part by leveraging disproportionate access to one of the state's scarcest and most vital resources: water.

Through The Wonderful Company, the Resnicks own more than 175,000 acres of farmland, including over 80,000 acres of almonds and pistachios—two of the most water-intensive crops in agriculture. According to estimates, Wonderful uses around 150 billion gallons of water per year, enough to supply San Francisco for an entire decade. The company claims less than 1% of the state's water use and says most of that comes from long-term land-based rights, not short-term purchases. But even so, their financial ability to buy water when needed often drives prices higher in a strained market.

At the heart of the controversy is the Kern Water Bank, a 32-square-mile underground reservoir in Kern County that can store up to 1.5 million acre-feet (roughly 488 billion gallons) of water. The Resnicks, through a private entity called Westside Mutual Water Company, own a 57% stake in the bank. The water is used to recharge aquifers and support their orchards during dry years. While their ownership stake is legal and stems from a 1994 agreement known as the Monterey Amendment, critics argue the deal privatized what should have remained a public resource. Water law analysts note that the Kern Water Bank was originally funded and developed by the state using taxpayer dollars before control was transferred, under opaque circumstances, to a mix of private interests—including the Resnicks.

Environmental advocates argue this move allowed the couple to "bank" public water and use it as a drought hedge, all while surrounding communities—often poor, rural, and heavily Latino—face water insecurity. In some areas of the Central Valley, residents rely on trucked-in water because their wells have run dry. "The Resnicks are so dominant," said environmental historian Char Miller. "The disempowered communities are at the other end of a scale that is tipped mightily against them."

In early 2025, this longstanding controversy turned into a viral firestorm when conspiracy theories began circulating online falsely claiming the Resnicks were "hoarding water" during the deadly Los Angeles wildfires. Some posts went so far as to claim they owned "60% of the water in California"—a statement that is factually false and grossly misleading. In reality, the Resnicks control 57% of one regional water bank, not 60% of the entire state's supply. California moves over 40 million acre-feet of water annually, and the Kern Water Bank represents a small fraction of that total.

Experts were quick to debunk the claims. Officials from the California Department of Water Resources, UC Davis, and the Kern Water Bank Authority confirmed that Los Angeles had adequate local water supplies for firefighting efforts. The issue, they explained, wasn't water availability—it was water pressure and infrastructure. "The logistical and operational needs required to move water from a water bank in Kern County to Los Angeles in a timely manner can only be suggested by those who aren't informed on how water infrastructure works," said Joe Butkiewicz, general manager of the Kern Water Bank.

Beyond misinformation, the online attacks against the Resnicks also took on an anti-Semitic tone. Several widely shared posts accused the couple of maliciously profiting from disaster, invoking conspiracy tropes common in far-right online communities. A spokesperson for The Wonderful Company called the claims "uninformed, discredited, and false," and pointed out that Wonderful employees in Los Angeles had also lost homes in the fires. The company donated $10 million to wildfire relief, including $1 million to the Los Angeles Fire Department Foundation.

Still, the broader discomfort remains. Critics argue that the consolidation of water rights into the hands of private billionaires—regardless of legality—poses long-term risks for equity and sustainability, particularly in the face of climate change. "Assets like this that were once in public control and now are in private control need to be returned to the public," said Alexandra Nagy of Food & Water Watch. "Especially with climate change and in moments of drought, that's when corporate interests take advantage and push their agenda the hardest."

The Resnicks argue they've been responsible stewards of their resources. They point to their use of advanced drip irrigation, their role in developing climate-resilient farming methods, and their record-setting $750 million donation to Caltech for climate research. They also fund health clinics, schools, parks, and college scholarship programs in the Central Valley.

But their central role in California's water economy remains deeply polarizing. Whether viewed as forward-thinking agricultural innovators or aggressive players in a broken water system, one thing is clear: the Resnicks have more influence over how California grows—and waters—its food than almost anyone else.

/2014/02/sl.jpg)

/2010/04/graeme-hart2.png)

/2009/09/otto2.jpg)

/2012/08/bill-wrigley.jpg)

/2020/08/melinda.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)

/2014/02/sl.jpg)

/2010/04/graeme-hart2.png)

/2019/09/GettyImages-515758004.jpg)

/2011/12/CNW-Man-1.png)

/2013/12/Anders-Holch-Povlsen.png)

/2012/08/bill-wrigley.jpg)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)