When Valentino Garavani died this week at 93, it quietly closed the final chapter of an era that once defined European fashion. Valentino had already stepped away years earlier, as had Jean-Paul Gaultier, who retired from ready-to-wear, and Giorgio Armani, who died in September. One by one, the titans of late-20th-century luxury either exited the stage, sold their empires, or became legends rather than operators.

Only two never left.

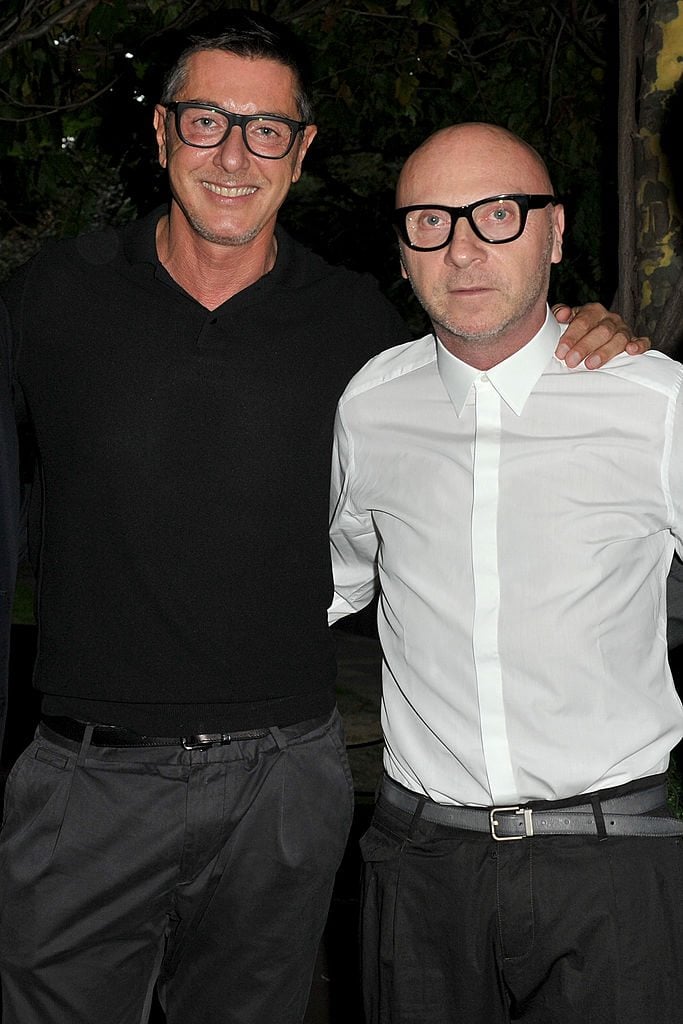

Dolce & Gabbana remains founder-controlled, privately held, and creatively dominated by the same two men who launched it four decades ago. Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana are not emeritus figures or ceremonial chairmen. They still sign off on collections. They still decide campaigns. They still run the business. And today, they are richer than ever, each with a net worth of $3 billion, presiding over a multibillion-dollar fashion empire that simply refused to die.

That fact alone would be remarkable. What makes it extraordinary is how unlikely it once seemed.

This is the same brand that, in 2013, appeared to be in free fall. Its founders were convicted in an Italian court. They were sentenced to prison. Headlines openly speculated about whether the company could survive if its creators were forced into house arrest or jail. Years later, just as that legal cloud finally lifted, the brand detonated another crisis, this time cultural, when a backlash in China wiped out goodwill in one of the most important luxury markets on Earth almost overnight.

The story of Dolce and Gabbana over the last decade is one of the most improbable second acts in modern fashion history. To understand how they pulled that off, you have to go back to the beginning. The year was 1985…

Stefano Gabbana (L) and Domenico Dolce (Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images)

The Bedsheet Runway

The year was 1985, and the "stage" was little more than a desperate improvisation. Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana had no money for professional models, so they called their friends. They had no money for a backdrop, so they pulled a bedsheet from their own apartment and hung it as a curtain. When the lights came up at Milan Fashion Week, the presentation looked less like the birth of a global luxury house and more like a last-ditch gamble by two designers who were almost out of options.

That scrappiness was not accidental. It was the product of two very different men colliding at exactly the right moment. Dolce, the quiet Sicilian, had grown up immersed in tailoring, learning the discipline of construction and fit in his father's small shop. Gabbana, louder and more instinctive, came from a background in graphic design, with an eye for imagery, attitude, and provocation. Where Dolce focused on how a garment was made, Gabbana focused on how it would be seen.

Together, they rejected the dominant fashion language of the time. Instead of chasing Parisian minimalism or corporate polish, they looked backward to Italy's own past. Black-and-white cinema. Postwar sensuality. Catholic symbolism. Southern Italian femininity that was strong, sexual, and unapologetically visible. Out of that vision came what the fashion press would later call "The Sicilian Dress," a silhouette that felt less like a trend and more like a statement of identity.

Commercial success did not arrive overnight. Their first collections struggled to sell. At one point, a canceled fabric order nearly killed the business before it had properly begun. The brand survived in part because Dolce's family quietly stepped in to help cover costs, buying the time the designers needed to produce another collection. By the late 1980s, that persistence began to pay off. Editors noticed. Buyers followed. The aesthetic started to spread.

Building an Empire Without Selling Out

By the early 1990s, Dolce & Gabbana had crossed the line that separates promising designers from serious players. Their collections were no longer niche statements admired by editors. They were commercial forces. Women wanted the dresses. Men wanted the suits. Celebrities wanted the association. What had once been a distinctly Sicilian fantasy was quickly becoming a global uniform for confidence and excess.

Crucially, the duo made a decision that would shape everything that followed. They did not sell.

At a time when many European fashion houses were being absorbed into sprawling luxury conglomerates, Dolce and Gabbana kept their company private and tightly controlled. There was no corporate parent to answer to, no quarterly earnings calls dictating creative direction, no outside executives nudging the brand toward safe compromises. Creative control and business power stayed where they believed it belonged: with the founders.

Expansion came fast, but it was purposeful. Womenswear remained the emotional core, but menswear became a major pillar, especially in Italy and the United States. Accessories followed, then eyewear, fragrances, and an ever-growing web of licensing deals that allowed the brand to exist everywhere from high-end boutiques to glossy department stores. Dolce & Gabbana was no longer just a label. It was an ecosystem.

Their aesthetic only grew more extreme as their influence expanded. The clothes leaned harder into sexuality. Campaigns grew louder and more confrontational. Catholic iconography mixed freely with overt sensuality. Family, heritage, and spectacle became recurring themes. Critics sometimes accused them of excess or caricature. Customers rewarded them anyway.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Dolce & Gabbana had achieved something rare in fashion. They were both culturally dominant and financially formidable. Madonna adopted the brand as a personal uniform. Supermodels became fixtures of their campaigns. Red carpets turned into unofficial runways. The company's revenues climbed into the billions, and the founders became fixtures of the global jet-set.

As the brand grew more valuable, its structure grew more complex. Intellectual property, licensing rights, and corporate ownership became just as important as hemlines and silhouettes. Decisions once made at a kitchen table were now made in boardrooms with lawyers and accountants.

It was during this phase, at the height of their power and certainty, that the choice was made that would later nearly destroy everything they had built.

Rise and Fall of Dolce & Gabana / Harold Cunningham/Getty Images

The Tax Case That Almost Ended Everything

In 2004, Dolce and Gabbana restructured ownership of key intellectual property tied to the brand, transferring control to a Luxembourg-based holding company. To their advisors, the move was framed as a legitimate corporate transaction involving brand rights. To Italian prosecutors, it looked like something far more sinister.

Authorities later alleged that the deal grossly undervalued the brand and allowed the designers to avoid declaring more than $1 billion in taxable income in Italy. For years, the dispute simmered quietly in the background, barely noticed by the fashion world as sales continued to climb and the brand's profile grew ever larger.

Then, in 2009, the charges became public.

Italian prosecutors accused Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana of tax evasion on a staggering scale. The case dragged on for years, growing more ominous with each court appearance. In 2013, it reached its most dramatic point. A Milan court found both men guilty. Each was sentenced to 18 months.

Convicted, Then Cleared

Dolce and Gabbana responded with fury and defiance. They insisted they were being scapegoated. They framed the prosecution as an attack on Italian creativity and entrepreneurship. At one point, they shuttered their Milan boutiques, restaurants, and cafes for days in protest.

Stefano Gabbana, never shy about confrontation, gave interviews dripping with indignation. Domenico Dolce, typically more reserved, stood firmly beside his partner. Both men rejected the idea that they were thieves or tax dodgers. They argued they lived in Italy, paid taxes in Italy, and had no intention of fleeing abroad.

For the first time since their improvised debut in 1985, the future of Dolce & Gabbana genuinely looked uncertain.

Then, almost as abruptly as the crisis had erupted, it evaporated.

Italy's highest court ultimately overturned the convictions, annulling the sentences and bringing the criminal case to an end. There would be no prison. No house arrest. No dramatic downfall. While tax authorities continued to pursue financial claims, the existential threat disappeared with little fanfare.

The Backlash the Courts Couldn't Stop

If the tax case represented a traditional business scandal, the next crisis was something far more modern and far more dangerous. It was cultural. It was global. And it moved at a speed no courtroom ever could.

In 2018, a promotional campaign ahead of a planned Shanghai runway show ignited a firestorm. Videos intended to be playful were widely interpreted as offensive. Messages attributed to Stefano Gabbana circulated online. Chinese celebrities withdrew their support. The show was canceled outright.

Within days, Dolce & Gabbana had become a case study in how quickly a luxury brand could be exiled from one of the most important consumer markets in the world. Retail partners distanced themselves. Online outrage snowballed. The damage was immediate and visible.

How a "Canceled" Brand Kept Making Money

For all the noise, something unexpected happened. The business did not collapse.

While China represented a major growth opportunity, it was not the entirety of Dolce & Gabbana's revenue. The United States, Europe, and other Western markets continued to buy the brand's products. Wholesale distribution, licensing, and fragrances provided ballast. Beauty, in particular, became an increasingly important engine.

Dolce & Gabbana invested heavily in controlling more of its operations internally, even at the cost of short-term profitability. The company absorbed expenses, expanded categories, and quietly kept compounding. Online outrage proved volatile. Revenue proved more resilient.

Fashion, it turned out, could be unforgiving socially while remaining durable financially.

The Kardashian Detour Back to the Mainstream

The brand's path back into the cultural conversation did not come through apologies or rebranding. It came through exposure.

In 2023, Kim Kardashian curated a Dolce & Gabbana runway show built around the brand's own archives. The collaboration reframed the label through nostalgia rather than controversy. It reminded audiences why the designs had mattered in the first place.

A later collaboration with Kardashian's SKIMS brand reinforced the message. This was not a desperate attempt at relevance. It was validation. The brand had found a way back into mainstream visibility without pretending the past hadn't happened.

Richer, Older, and Still Unkillable

Today, Dolce & Gabbana is once again discussed less as a scandal magnet and more as a business. The brand generates billions in annual revenue. Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana each have a net worth of $3 billion.

The company has explored options ranging from minority investors to a potential public listing. Beauty remains a key growth focus. China remains unfinished business. But the arc is unmistakable.

They were convicted, canceled, and written off more than once. And yet, four decades after a bedsheet curtain improvised their first show, Dolce & Gabbana remains intact, independent, and enormously profitable.

In fashion, survival is rare. Survival at this scale is almost unheard of. Dolce and Gabbana managed both.

/2022/11/dolce.png)

/2021/05/amani.jpg)

/2025/09/armani.png)

/2010/12/Valentino-Garavani.jpg)

/2011/07/Pierre-Cardin.jpg)

/2015/08/cook.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/P-Diddy.jpg)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)