On a blazing hot Gainesville summer day way back in 1965, the coaches of the University of Florida football team found themselves facing an unusual problem. Their players kept passing out during practices due to heat exhaustion.

Desperate for a solution, Assistant Coach Dwayne Douglas and Head Coach Ray Graves made a special request to scientists at the school's College of Medicine. They requested that the doctors investigate was causing the heat-related illnesses of athletes working in the hot climate, and potentially create a solution. Those coaches didn't know it at the time, but this simple request would eventually spawn one of the most commercially successful sports drinks of all time. A drink that, despite having knockoffs and imitators, still generates more than $3.3 billion a year in revenue.

As you probably know by now (especially if you read the titled of this article), the invention we are talking about is Gatorade. Also known as the official drink of the NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL, MLS and even Professional Volleyball. What you may not know is that because Gatorade was invented by teachers using school labs, grants, and students as resources, the University should have owned a majority of the product that today carries their mascot's name. But, to use sports lingo, school officials dropped the ball. As if that wasn't dumb enough, the teachers who invented Gatorade tried once more to throw the school a bone by selling them the rights for $10,000. Once again, the ball was dropped. Thanks to this stupidity, four teachers went on to make an absolutely astonishing amount of money. Here's the full story…

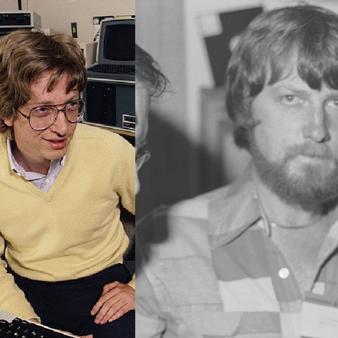

Getty Images

Inventing Gatorade

After being commissioned by the football coaches, a team of researchers led by Dr. Robert Cade set about on a four month quest to understand and solve the problem of players passing out from heat exhaustion. The other scientists assisting Dr. Cade were Dr. Dana Shires, Dr. Alex de Quesada and Dr. Jim Free.

Their eventual conclusion was that the players were passing out because practicing football in 90 degree heat was causing them to burn through extraordinary levels of carbohydrates and electrolytes.

Their solution was simple: Create a drink that contained a replenishing amount of carbs, water and electrolytes. Why a drink? Because a liquid beverage seemed like the perfect delivery method for athletes on the sidelines of a football field. The biggest early challenge was making the drink taste good.

Early versions of Gatorade were made up of water, sodium, sugar, potassium, phosphate, and lemon juice. Ten players tested the beverage during games and practices, and it appeared to solve the problem. At first, the drink was called called "Cade's Cola," then "Cade's Ade," and then some brilliant, yet forgotten player, made the now obvious leap to "Gatorade."

Gatorade received its first big test during the 1965 season in a game against the LSU Tigers. It was a particularly scorching day when temperatures in Gainesville peaked at 102 degrees. During the second half, the LSU players began to slowly shut down and fade, but the Gators were still running strong. At this point, Head Coach Ray Graves was convinced Gatorade worked, and he asked that Dr. Cade produce mass quantities of the drink for every game for an indefinite period. Two years later, the team even claimed that Gatorade was responsible for their first Orange Bowl win in 1967 against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets. When asked what contributed to his team's loss, Yellow Jackets Coach Bobby Dodd admitted, "We didn't have Gatorade. That made the difference."

Not long after that Orange bowl victory, Dr. Cade approached the school and offered to sell them 100% of Gatorade for $10,000. He also requested that the school help him mass-market the drink. The University declined. By the way, $10,000 is the same as around $75,000 today after adjusting for inflation.

After being rejected by the school, Dr. Cade approached a canned food packaging company called Stokely-Van Camp. His offer this time was to sell 100% of Gatorade for $1 million (around $7.3 million today). Not believing the drink would have the mass-appeal Dr. Cade envisioned, Stokley-Van Camp counted by offering $25,000 up front plus a $5,000 bonus and a five cent royalty on every gallon that was eventually sold. Dr. Cade accepted. He would have no idea just how lucky he was to be given that counter offer.

Stokley-Van Camp began producing the drink almost immediately. Around the same time they also paid the NFL $25,000 to be the official drink of the league. Sales began to explode nationwide. And as sales exploded, some senior officials at the University of Florida began to regret their decision to not buy 100% of Gatorade for $10,000.

So the school sued.

According to Dr. Cade's biography:

"They [the school] told me Gatorade belonged to them and all the royalties were theirs. I told them to go to hell. So they sued us."

The lawsuit was filed in 1971. In the lawsuit, the University (accurately) pointed out that Dr. Cade and his fellow researchers used school labs, equipment and even the mascot name to create Gatorade.

There were two problems with U of F's case.

#1) Technically speaking, Dr. Cade and his three cohorts were using federally funded grants provided by the National Institute of Health to run their lab and pay for their research.

#2) Typically, all researchers of the University of Florida were required to sign a waiver that granted the school 75% of all earnings generated during their employment. For some reason, Dr. Cade never signed that waiver.

The United States government also briefly attempted to sue for a share of the profits but eventually backed off after Dr. Cade agreed to relinquish the rights to three of his patents.

After a very bitter three-year legal battle, the case with the U of F was finally settled in 1972. The settlement allowed Dr. Cade and some other early partners to keep the majority of the rights, while also giving the University of Florida a 20% stake in Gatorade profits going forward.

This is how the Gatorade Trust was born.

The brand was acquired by Quaker Oats in 1983 for $220 million. In 2001, PepsiCo bought Quaker Oats for $13 billion (Gatorade was Pepsi's primary acquisition target in the transaction). This acquisition gave Gatorade yet another new home, plus a nearly unlimited marketing budget and access to a distribution network that spanned 80 countries.

Royalty Cash Register

Between 1972 (when the Gatorade Trust was established) and today, the University of Florida has received $281 million in royalties from Gatorade.

How'd those four doctors end up making out? This weekend marks the 50th anniversary of when Gatorade was first used during a game by University of Florida football players. Over those 50 years, Dr. Robert Cade, Dr. Dana Shires, Dr. Alex de Quesada and Dr. Jim Free received a combined $1.1 BILLION in Gatorade royalties.

Dr. Cade didn't hold a grudge against the U of F for suing him. He actually spent the final 25 years of his life as a professor emeritus of nephrology (study of the kidney) at the University. He was also instrumental in creating a philanthropic branch of Gatorade, which today delivers thousands of free bottles to third world countries every year to help fight dehydration. Though he lived his entire life in the same six bedroom Gainesville house he bought in 1965, Dr. Cade did use his wealth to indulge one unique passion: Rare vintage Studebaker automobiles. By the time Dr. Cade died in 2007, his collection contained more than 100 Studebakers.

Just seven months before his death (ironically from kidney failure), Dr. Cade was inducted into the Florida Athletics Hall of Fame. His induction was capped, appropriately, when a group of fellow professors dumped a cooler of Gatorade over Dr. Cade's head. No joke. That actually happened. He was 79 years old at the time.

One more fun fact!

Gatorade isn't the only product that has earned the University of Florida millions in royalties. The school has earned approximately $264 million from a product called Trusopt which is used in the treatment of glaucoma, and $30 million from a product called Sentricon which kills termites.